In this mini lesson I’d like to demonstrate a) some Markdown syntax, b) how you run and format R code, and c) how to render R figures. If you read the Course Description you have already seen examples of embedded tables. Remember, our primary goal is to create R Markdown documents that capture code, data, and data products.

R Markdown integrates the concepts of literate programming and reproducible research, which, in addition to explaining or documenting itself, also allows others (including an original investigator) to reproduce a data analysis or other research result.

The page you are reading is a basic R Markdown document with some examples of the functionalities you can incorporate. Building a site like this is very much an attainable goal in a short amount of time. Some of the examples presented below are unique to R Markdown while others are included to demonstrate cross-platform functionality. I wrote this as if it were a report; to give you a general sense of what these documents look like. I would like you to look at the raw R Markdown code for this page (available here) before, during, and after you read the post. Doing this will give you a feel for some of what you will be doing. Take a look at the raw document, paying special attention to the code, not the text. Understanding what all of this code means is part of the course. Consider this a prelude ;)

Markdown

First let’s talk about the Markdown part of R Markdown. Markdown is a lightweight markup language with plain-text-formatting syntax. What this means is that Markdown is easy-to-write using any generic text editor and easy-to-read in its raw form. When you render a page or document, R Studio translates the Markdown syntax to HTML code and the document becomes a web product. Let me give you a few examples of HTML vs. Markdown code. For each example, I will show you the code (displayed in grey code blocks) followed by the output.

Headers

Many of the headers on this page are Level 2. There are usually 6 header levels. Level 1 is the largest and mostly used for titles, like the one atop this page. OK. So, say we want to write a header in HTML. We need to wrap the text in h2 HTML tags like this <h2>Second Level Header</h2> and we get a

Second Level Header

To get the same result in Markdown we use double hash tags like this ## Second Level Header (note the space between the second # and first letter is necessary).

Second Level Header

Level 3 is ### and so on. Seems trivial but imagine doing this a few dozen times. Typing out the HTML tags is kind of annoying. Let’s take a look at a two more examples of HTML vs Markdown: ordered lists and hyperlinks.

Ordered Lists

HTML

To write an ordered list in HTML you must enclose each list item in the <li> tag and wrap the whole list in the <ol> tag.

<ol>

<li>Rod Carew</li>

<li>Mariano Rivera</li>

<li>Carlos Lee</li>

</ol>- Rod Carew

- Mariano Rivera

- Carlos Lee

Markdown

In Markdown you just write the list with numbers.

1. Rod Carew

2. Mariano Rivera

3. Carlos Lee- Rod Carew

- Mariano Rivera

- Carlos Lee

If you wanted an unordered list, you would begin each line with a single asterisk (*) instead of a number.

Hyperlinks Links

You will probably use hyperlinks a lot in your projects. Let’s take a look at the hyperlink syntax.

HTML

To code a link in HTML you need to use the <a> tag and then put the display text in between the tag and the actual link. So here is the code followed by the output.

This is a <a href="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Islamic_geometric_patterns">link</a> to awesome geometric patterns.This is a link to awesome geometric patterns.

Markdown

To code a link in Markdown you simply put the display text between square brackets followed by the link in parentheses.

This is a [link](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Islamic_geometric_patterns) to awesome geometric patterns.This is a link to awesome geometric patterns.

Each example above gives the same result but with Markdown we use less, and more intuitive, code. There are many other examples where you will use Markdown syntax for general formatting like bold text (wrapped in **), italics (wrapped in *), and inline code (wrapped in back ticks ``). In the text below is an example of block text. To get this effect you simply use the \(>\) symbol at the beginning of the line.

So, Markdown is pretty straightforward. Howeve, it is important to note that Markdown can only take you so far. Markdown is great for basic formatting but once you get into more complicated styles and formating, you will need HTML and CSS. Don’t worry, we will do some of that too.

MathJax

Next, I wanted to show you an example of a different type of text formatting that can be added to your documents, specifically using Mathjax to write mathematical equations.

Mathjax is a cross-browser JavaScript library that displays mathematical notation in web browsers, using MathML, LaTeX and ASCIIMathML markup. There is no need for end user software installation. We can render right in the HTML.

Mathjax has its own lightweight code that is usually wrapped in dollar signs ($). If you hover over your text while you write it, a little preview window should pop up that shows you what the final equation will look like. This way you can tweak the look before you render the document. Mathjax code can be written straight in the document. When R Studio renders the document it will see the $, interpret it as Mathjax code, and translate the code to elegant Mathjax typography.

Here is the notation for one of my favorites, the Lorenz equations. I am showing the actual code here for demonstration purposes only. Normally this would be hidden.

So this awkward looking code…

$$

\begin{cases}

\dot{x} = \sigma(y-x) \\

\dot{y} = \rho x - y - xz \\

\dot{z} = -\beta z + xy

\end{cases}

$$becomes these elegant equations.

\[ \begin{cases} \dot{x} = \sigma(y-x) \\ \dot{y} = \rho x - y - xz \\ \dot{z} = -\beta z + xy \end{cases} \]

Nice. You can also use simple inline expressions where equations like this $e^{i\pi} + 1 = 0$ looks like this \(e^{i\pi} + 1 = 0\) or this equation $f(k) = {n \choose k} p^{k} (1-p)^{n-k}$ is rendered like this \(f(k) = {n \choose k} p^{k} (1-p)^{n-k}\).

R Markdown

Now that we know a little about Markdown, lets add the R part. This is where the true power of this whole concept comes into view for reproducible and transparent data science.

R Markdown is a an R package—a set of tools deeply embedded in R Studio. R Markdown combines Markdown text with R code to create documents containing formatted text plus results of executing R code.

I hope you can see that there is nothing too complicated about the concept. Lets illustrate how we incorporate R code in a Mardown document with a quick toy example.

Most of the time you run R code in an R Markdown document you do it within a special internal environment called a code chunk. The specific formatting of the chuck tells R Studio that this is R code and it needs to be run as code and not rendered as text.

To run R code in your document there is a particular syntax you must use when creating the code chunk. The format of the code chunk is as follows:

- Begin with three back ticks (on a mac this is the upper left key), then open curly bracket, then the name of the language (in this case

r), followed by a closed curly bracket, and finally a line break. This tells R Studio this is R code. - An optional but best practice step is to also include a unique chunk name and chunk options. We will discuss both of these in later lessons.

- On subsequent lines you write the R code like normal.

- Within the chunk you can add comments by beginning a line with a hash tag. R Studio will not interpret this as code.

- Add a final line break. End with three back ticks.

Here is what the example looks like in code chunk format.

```{r chunk name, chunk options}

# Start with three back ticks

# add the r tag inside curly brackets

# Name the chunk and add chunk options

# run some commands

library(ggplot2)

summary(cars)

# And maybe make a plot

qplot(speed, dist, data=cars) + geom_smooth()

```And this is what happens when this code is executed by R Studio. First, the command library(ggplot2) is executed, then a summary is produced with the summary(cars) command, and finally a plot is rendered using the command qplot(speed, dist, data=cars) + geom_smooth().

## speed dist

## Min. : 4.0 Min. : 2.00

## 1st Qu.:12.0 1st Qu.: 26.00

## Median :15.0 Median : 36.00

## Mean :15.4 Mean : 42.98

## 3rd Qu.:19.0 3rd Qu.: 56.00

## Max. :25.0 Max. :120.00

## `geom_smooth()` using method = 'loess' and formula 'y ~ x'

In the examples below, you will notice that some of the R code shows the code chunk header—in other words the line ```{r, chunk name, chunk options}```—while other R code chunks do not. Under normal circumstances, the code chunk header is never shown, only the actual R code. I included the chunk headers for demonstration purposes only.

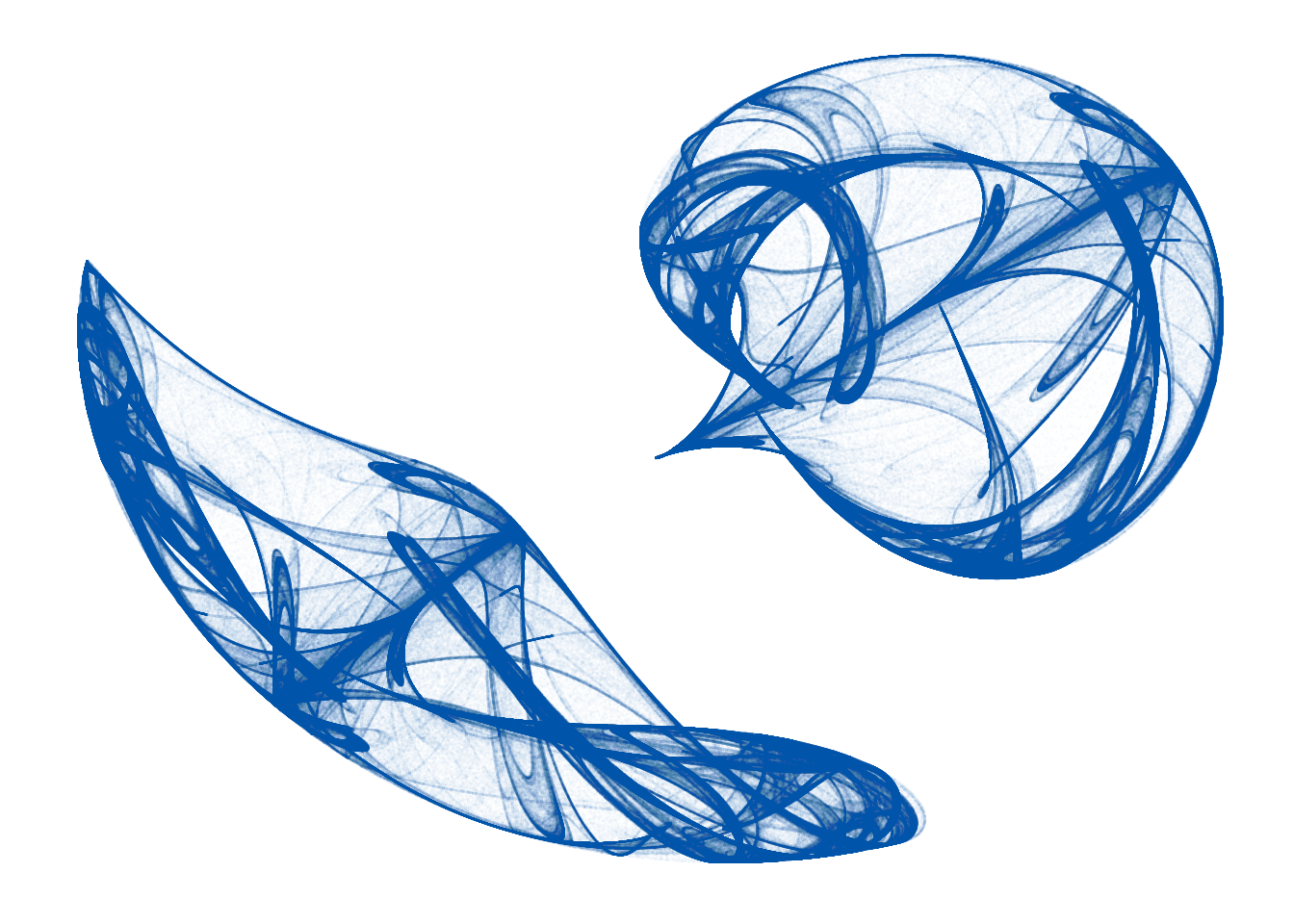

A Better Example: Clifford Attractors

Great. Now let’s look at something a little more interesting.

I really like iteration, chaos, and fractals. So I was pretty jazzed to find this R code by Fronkonstin for plotting Clifford Attractors, a type of strange attractor discovered/invented by Cliff Pickover. Clifford Attractors are made by iterating two trigonometric functions (initial conditions \(x = 0\) & \(y = 0\)) with four variables (\(a, b, c, d\)). The code will generate 10,000,000 points (iterates) and render the results as a pretty sweet graphic.

Here is the equation I used in the script below:

\[ \begin{cases} x_{i + 1} = sin(ay_i) - cos(bx_i) \\ y_{i + 1} = sin(cx_i) - cos(dy_i) \end{cases} \]

With these variables:

\[ \begin{align*} a = -1.164, \ b = 1.41, \ c = -1.42, \ d = -1.6 \ \end{align*} \]

The equations and the variables can be tweaked to produce a range of beautiful structures. Now we can run the R code and render the results in the document. You can run this exact code in a regular R terminal except in R Markdown we decorate the code with the code chunk syntax described above.

The R script here is a bit long so let’s use some simple HTML to fold the code. That way the code is available but not taking up a bunch of real estate. We will learn about code folding in the course.

Show/hide Clifford Attractor code

```{r, clifford, cache=TRUE}

opt <- theme(legend.position = "none",

panel.background = element_rect(fill="white"),

axis.ticks = element_blank(),

panel.grid = element_blank(),

axis.title = element_blank(),

axis.text = element_blank())

cppFunction('DataFrame createTrajectory(int n, double x0, double y0,

double a, double b, double c, double d) {

// create the columns

NumericVector x(n);

NumericVector y(n);

x[0]=x0;

y[0]=y0;

for(int i = 1; i < n; ++i) {

x[i + 1] = sin(a*y[i]) - cos(b*x[i]);

y[i + 1] = sin(c*x[i]) - cos(d*y[i]);

}

// return a new data frame

return DataFrame::create(_["x"]= x, _["y"]= y);

}

')

# Parameters:

a = -1.164

b = 1.41

c = -1.42

d = -1.6

df <- createTrajectory(10000000, 0, 0, a, b, c, d)

```And now we plot the results and save a png copy just in case. With so many iterates this will take a minute or two to run. During the course, we will discuss the option caching code that takes a long time to run.

ggplot(df, aes(x, y)) +

geom_point(color="#007da2", shape=46, alpha=.01) +

opt +

theme(panel.background = element_rect(fill = '#ffffff'))

Amazing what a couple of simple trigonometric functions iterated 10,000,000 times can do.

If you have regular old R installed, try running the scipt which is available to download here: Clifford code. There is a small description on the top. You may need to install some libraries.

And that’s it for this mini lesson. The next lesson will focus primarily on setting up your working environment. This mainly entails installing the tools and libraries we will need throughout the course. Others will be added as needed. I will also post a general course outline soon.

As we move forward keep your out for the icon. This is where you can find a link to the raw code for the page on GitHub. The little button on the top of the page (the one that looks like a cat) will take you to the main GitHub repo for this site.